Italian Lombards

In English ✦ Lietuviškai

In her latest book, El Camino de los Godos (The Way of the Goths), philologist Jurate Rosales (Jūratė Statkutė), who specializes in ancient Romance languages, has written a chapter entitled The Lombards of Italy. Since the book has not been published, I will copy the entire chapter here.

A separate and important chapter should be devoted to the Balts of the Oder River, whose history was noted and began to be researched by Valentinas Juškevičius, a GIS (Geographic Information Systems) specialist. His attempt to distinguish the influence of the Baltic languages is particularly valuable because it eliminates the possibility of Germanic influence in Italy. In addition, we again encounter the same error that has misled historians so many times, as the word Scandinavia is repeated, when in fact it should have been Skančia or Skandija, and the geographical location is undoubtedly the island in the Curonian Lagoon.

According to Juškevičius’ research, the Lombards who arrived in Italy from the Oder River valley, whose earlier name was Vinili and who apparently did not reach the mouth of the Oder and remained in the middle region of the river, were not Germanic tribes and their names were Baltic.

When the Ostrogoths withdrew from Italy after the arrival of the Byzantine armies, Byzantine rule did not last long, and soon the lands of northern Italy were occupied by the Baltic tribes of the Lombards. It is not known whether the Lombard tribes had already settled in Italy as allies of the Ostrogoths. What is clear is that their presence in northern Italy is a historical fact with dates, names, and descriptions of events beginning in the 6th century.

GIS specialist Juškevičius writes that the Lombards were not Germanic tribes and explains why he believes this to be true. I am reproducing Juškevičius’s report in its entirety, the value of which will become very important in time, when it becomes clear, just as is now happening in Spain with the western Goths, that in Italy too there were only Balts who had permanently preserved the legacy of the eastern Goths. Lithuanian universities will probably have to trace the influence of the Baltic languages not only in Spain, but also in Italy.

It should be emphasized that the Western Goths settled in Spain, while the Eastern Goths came to Italy, and as we already know from earlier historical knowledge, mostly taken from Jordanes writings, they all considered themselves members of one nation, judging by the many historical events in which mutual assistance is always emphasized, especially in times of war or danger.

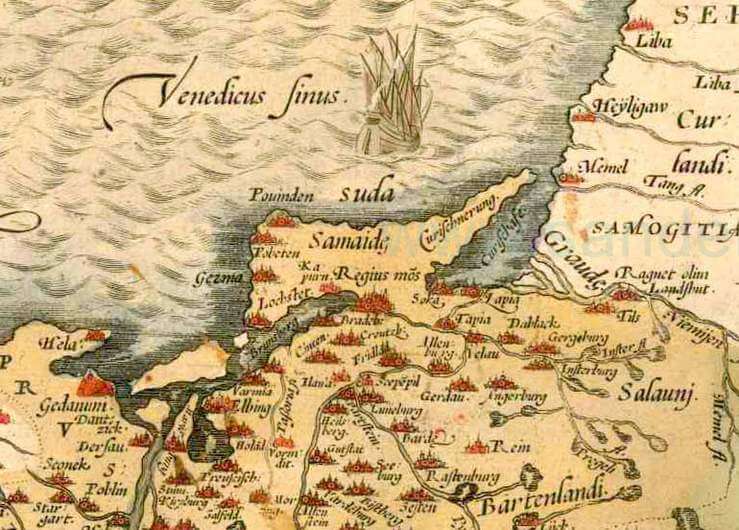

So, this time, we have the text of the first history of the Lombards written by Paolus Diaconus between 787 and 789, and a clear indication of the Lombards’ origin, that they came from an island, but there is no mention of ships or migration to the mainland. However, judging by the description of where the Vinils came from, the information mentioned coincides with the Curonian Lagoon area.

Jūratė Rosales: „The Way of the Goths“ (El camino de los godos) 2022 year.

I have never been interested in place names nor Lombards myself, and only became interested in 2008, when I worked and lived in Italy, in the province of Lombardy, from 2008 to 2013. Matteo Salvini, Italy’s current Deputy Prime Minister, was then working for Radio Padania Libera in the northern Italian city of Milan. At that time I was commuting 20 kilometers to and from my work every day, so I had a lot of nice time listening to this radio. Salvini’s transmissions covered both political events and interesting observations on Italy’s past. His broadcasts were notable for their profound insights and wealth of data. Once, while talking about Lombardy, he wittily mocked scholars who attributed their place names to Germanic heritage. “There is not a trace of Germanic heritage here!” he said. I thought: something might be wrong with those place names, because they did not seem Germanic to me either. That was when the first bell rang for me.

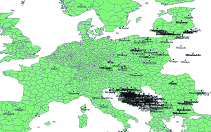

The places named Bards (also known as Barts, Berts, Berds) are rare in German-speaking countries, although the word “Langobards” is most often associated with these roots. Such place names could be linked to origins and settlements of Lombards. The following maps are created automatically, based on the GeoNames database of geographical names maintained by the U.S. government „GeoNames“.

European distribution of Bard- and Bart- root place names.

The bell rang a second time while riding in the back seat of a car, when I overheard a conversation about those place names between a local Italian and a German who had just arrived in the area. “This is your Germanic heritage” said the Italian pointing to the towns and their names as they passed by. “There is nothing Germanic here!” wondered the German. From then on, I began to doubt the Germanic origin of Northern Italian place names and took a deeper interest into Lombardy and Langobards.

Let’s start from the very beginning, with the main source of knowledge about Langobards: — „The History of the Lombards“. This is a book in Latin by the Benedictine monk Paolus Diaconus (Paolo di Varnefrido) from the end of the eighth century on the history of the Lombards, starting with mythical characters and ending with the death of King Liutprand in 743.

Scholars present this book as undeniable proof that the Lombards were Germanic. But what does it say? What evidence of Germanic origin does it provide? The current view among historians is that the Germanic peoples were the Goths, Lombards, Vandals, and other barbarians who came from the island of Scandza, which is Scandinavia.

Let us examine this work by Paolus Diaconus. Both authors, Jordanes in Getica and Diaconus in The History of the Lombards, say that the barbarian tribes set out on their journey to Italy from an island. Diaconus book does not mention that the Vinili (Lombards) crossed the Baltic Sea before arriving in Pannonia. It is stated that they simply left the island. Jordanes, on the other hand, states that after leaving the island, the Goths sailed along the coast for a long time. This is erhaps the only significant difference between the introductions to the two books.

The key passage in the book History of the Lombards which supposedly proves their Germanic origin, is as follows:

Similarly, the Vinili, that is, the Lombards, who later ruled Italy, were of Germanic origin, coming from an island called Scandinavia. Other reasons for their emigration are also mentioned.

Pari etiam modo et Winilorum, hoc est Langobardorum, gens, quae postea in Italia feliciter regnavit, a Germanorum populis originem ducens, licet et aliae causae egressionis eorum asseverentur, ab insula quae Scadinavia dicitur adventavit.

Paolus Diaconus: „Historia Langobardorum“, ca. 789.

Depending on the copy of this book (the original has not survived), the name of the island is written in various ways:

Scandin, Scandana, Scatinavia, Scladinavia, Scadinavia, Scandanavia.

The first part of the book mainly discusses the Vinili (ancestors of the Lombards). It mentions that they left the island, but does not mention any ships. It says that the island is not far out at sea, but visible from the shore, so it can be assumed that the Vinili left on horseback or on foot. The shore is flat, so the coast is flooded — marinis fluctibus propter planitiem marginum terra. And the coastline is curved — circonfusa. We would say: “The coast is flat, so sea tides and storm waves flood it (skandina – in Lithuanian language).” Question: where is such a place in Sweden? Answer: there is no such geographical location in Sweden. The book History of the Lombards describes the island as follows:

Although other reasons for their emigration were suggested, they came from an island called Skandinavia. Pliny the Younger also mentions this island in his book On the Nature of Things. Therefore, as those who have studied it have informed us, this island is not so much in the sea as it is surrounded by the waves of the sea due to the flatness of the surrounding shores.

Licet et aliae causae egressionis eorum asseverentur, ab insula quae Scadinavia dicitur adventavit. Cuius insulae etiam Plinius Secundus in libris quos De natura rerum conposuit, mentionem facit. Haec igitur insula, sicut retulerunt nobis qui eam lustraverunt, non tam in mari est posita, quam marinis fluctibus propter planitiem marginum terras ambientibus circumfusa.

Paolus Diaconus: „Historia Langobardorum“, ca. 789.

Looking at a map of the Baltic Sea, it is clear that the only island that fits this description is located in the flat southeastern part of the Baltic Sea, separating the Vistula estuary in Aistmares and the Nemunas estuary in the Curonian Lagoon from the sea. It is called Nerija, formerly known as Neringa, Nertia, Nercia, Nerčia, or otherwise Skandia, Skendzia. Probably together with Semba (Semva) in the middle. These two Lithuanian verbs, nerti and skęsti, are similar in meaning.

Opposite the mouth of the Vistula a curved island can be seen — both spits with Semba

(according to ancient beliefs).

All other islands are either far out at sea, not flooded, or not curved. All of this fits nicely with Jūratė Rosales’ insights and Jordanes excerpt from Getica. The word Scadinavia mentioned by Paolus Diaconus has no meaning in Swedish. In Lithuanian, it means a flooded, sinking area. The likely real names of these areas are: *Skandena, *Skenduonia, *Skęduo. Diaconus also mentions the place names Scoringa and Mauringa. He indicates that the Lombards lived there. However, these are not Germanic place names, as they end in a vowel, and the suffix -ing- is Baltic, as found in other placenames:

Neringa, Palanga, Alanga, Ablinga, Kretinga, Babrungas, Būtingė, Drubengis, Dubingiai, Kūlingė, Stabingiai, Notangai, Leipalingis, Nedzingė, Suvingis.

By the way, this does not contradict Jordanes Getica, both sources complement each other. Getica says that the island of Skandza is visible to the eye from the Vistula delta. Scandinavia is not visible to the eye from the Vistula coast.

This is situated on the bank of the Vistula River, which rises in the Sarmatian Mountains, in sight of Scandza and flows into the northern Ocean in a three-furrowed pattern, dividing Germany and Scythia.

Haec a fronte posita est Vistulae fluminis, qui Sarmaticis montibus ortus in conspectu Scandzae septentrionali Oceano trisulcus inlabitur, Germaniam Scythiamque disterminans.

Jordanes „Origen y gestas de los godos” Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

It is also worth noting the genetic studies of the Lombards. DNA samples failed to prove the Germanic origin of the Lombards. One of the latest studies was published in the scientific essay “A genetic perspective on Longobard-Era migrations“. Here is an eloquent excerpt from the essay:

A principal component analysis (PCA) on this expanded dataset highlighted the similarity between the Longobard culture graves of Szólád and medieval populations from Central Europe (Slovakia 800–1100 CE, Poland 1000–1400 CE) (Fig. 4). The Collegno individuals clustered midway between Slovakian and medieval samples from Southern Europe (Spain 500–600 CE, Italy 900–1400 CE).

Stefania Vai, etc: „A genetic perspective on Longobard-Era migrations“ 2019-01-16 „PubMed“ 647-656 p.

Scientists determined the origin of the main part of the samples (a total of 87 DNA samples were examined), which turned out to be most similar to people currently living in Poland and Slovakia. Did Germanic peoples live in those areas at that time? This is highly doubtful. The published summary also reveals that traces of Germanic DNA were indeed found, but they were buried further away from the main cemeteries and with wooden “weapons.” This suggests that these people were outcasts or of lower origin — this is precisely what is written in the conclusion of the scientific work.

Important information that helps us understand who the “barbarians” were can be found in the Italian medieval book “Lives of the Saints and Blessed Florentines.”:

written according to the barbaric custom of the time without the letter H.

scritto secondo l’uso barbaro di quel tempo senza la lettera H.

Giuseppe Maria Brocchi: „Vite de’Santi e Beati Fiorentini“ 1742 year, 91 p.

Thus, the author asserts that the “barbarians” did not use the sound H. In Lithuanian spelling, H was only legalized in the 20th century, under pressure from foreigners and newly “baked” intellectuals, and only in writing, not in speech. In early medieval Europe, only the Baltic languages did not have the H sound, and now Italian, French, Spanish, and other Romance languages do not have it either. How did this happen? Based on late Latin and early Italian writings, scholars only acknowledge that the H sound gradually disappeared from the language. Why did it disappear? And who were those “barbarians” who did not have the H sound in their pronunciation?

Current language dictionaries also reveal something to us. Scientists do not know why the H sound became silent. This uncertainty can be seen in French Dictionary Le Grand Robert.

the letter H became mute during the Empire time or at the beginning of the Germanic period due to the influence of the Greek language.

de la lettre lat. h, devenu muette dès l’Empire, ou du h aspiré initial germanique, de l’esprit rude en grec.

Le Grand Robert (ISBN 2850366730) III vol., 2001 year, 1631 p.

It is interesting to note how the Germanic and Greek peoples influenced the disappearance of the H sound, given that they themselves were carriers of it.

Let us examine the scientific work “Germanisms in the Lombard Diplomatic Code” (Germanismi editi e inediti nel Codice diplomatico longobardo 1998/1999 9 vol. 191-240 p.). “Germanisms” were collected from Latin documents written in the former Lombard kingdoms. None of the words found to be Germanic contain the letter H. Where, then, are the signs of Germanic origin? Is there even a single word of Germanic origin?

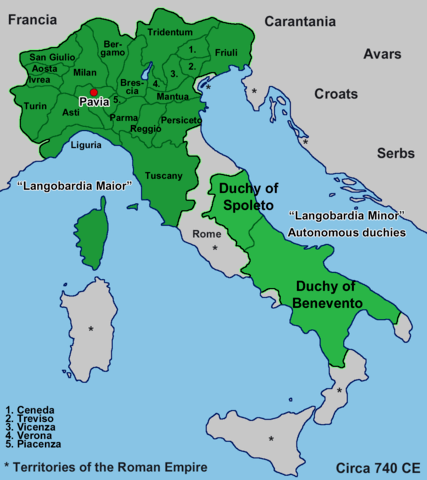

We can also touch upon the history of the last Lombard kingdom in Italy. The Kingdom of Benevento was located in southern Italy, and the Frankish king Charlemagne was unable to conquer it. The name of the last princess of the state of „Benevento Longobardorum“ was Sigelgaite (869-940). The suffix -aite is a purely Lithuanian suffix for a maiden name, which does not exist in other languages.

The Lombard Kingdom in Italy in 740.

Paulus Diaconus also mentions in his book History of the Lombards that the Slavs landed in the Apulia region near Siponto in 642.

When he was informed of this, Raduald quickly arrived and spoke to the newcomers in their own language.

Quod cum Raduald nuntiatum fuisset, cito veniens, eisdem Sclavis propria illorum lingua locutus est.

Paolus Diaconus: „Historia Langobardorum“, ca. 789.

Only the Balts and Slavs could understand each other at that time, while the Germans could not communicate with the Slavs.

The ruler of Benevento, Raudvaldis, is written in various ways: Raduald, Radovald, Radoaldo, Rodoaldo, Radualdo. And on the coin of another southern Lombard ruler of the state of Benevento, Grimwald III (Grimoald III), the words GRIM VALD are engraved. If this were a Germanic ruler, the inscription on the coin would mean FOREST. Such a word cannot be engraved on a coin; it is an inscription of Baltic origin, meaning ruler. Incidentally, the word „grimti“ can also be found in the Lithuanian dictionary.

A gold coin minted by Grimwald III in 792-806

In northern Italy, especially in the Po River basin, many place names can be understood in Lithuanian, and around Milan (Milano) and north of it, even about 90%. The famous Lithuanian linguist Kazimieras Būga once pointed out the Baltic place names there, but later retracted his findings (Aistiški studijai, vols. I-II). Here are a few examples of place names of Baltic origin in the Milan area:

Cairate, Gallarate, Gavirate, Linate, Ranco, Vimercate (Vilmercate 745), Meźźate, Carate, Scudellate, Rancate, Bardello, Ispra (Ispera 1145), Codate etc.

By restoring the lost diphthongs, the meaning of the names becomes understandable to Lithuanians and Latvians.

Dante Olivieri’s book Dizionario di Toponomastica Lombarda (Dictionary of Lombard Place Names), published in 1961, lists a great many Baltic elements. However, they are examined only from a Germanic perspective, with all place names being compared to Germanic words. Nevertheless, this book is an excellent source of old place names that can no longer be found on modern maps.

As soon as the Lombards arrived in the Po Valley, they renamed several major cities. The Latin names Mediolanum ir Ticinum pakeitė į Milano ir Papia (later Pavia). Geographic information system (GIS) queries can be used to see where else in Europe there are place names that begin with these four letters. Based on the results of these SQL (Structured Query Language) queries, we can guess where the Lombards came from. It is clear that the people who renamed these cities came from the Baltic and Slavic regions.

The distribution of place names Pavi- and Pawi-, Papi-, Mila- in Europe.

Here are all the names of Lombard kings in the light of Baltic words, the roots of which can be found and checked in the Lithuanian language dictionary on the Internet: www.lkz.lt.

Audoin, Alduin, Auduin, Audoin – alduoti – to sing, to chant

Alboin, Alboinus – ulbuoti, ulbenti – to chirp

Cleph, Clefi, Clepho – klepus – restless

Autari – taria – to talk

Ansvald – anas + valdo – he rules (to govern)

Agilulf, Agilolf, Ago, Agilulfus – agi + ulpas – a sound

Adaloald, Adalvald, Adelbald – adalnai + valdo – separatelly rules

Arioald, Ariovald – aro + valdo – an eagle rules

Rothari, Rothair, Rotari, Chrothar, Chrothachar, Rotharius – rota + taria – group (company) talk

Rodoald, Rodvald – roda + valdo – decision rules

Gaidoald, Gaidoaldus – gaidas + valdo – songs rules

Aripert – aro + pertas – born of an eagle

Perctarit, Perctarith, Berthari – pertaria – to convince

Godepert, Gundipert, Godebert, Godipert, Godpert, Gotebert – gundyti + valdo – tempt rules

Grimuald, Grimoald, Grimvald – krimsti + valdo – nurture rules

Garibald, Garivald – geri + valdo – to rule well

Alahis, Alagis – alalauti – to chirp

Cunincpert, Cunibert, Cunipert – kuningas + pertas – born of king

Liutpert, Liutbert – liūto pertas – born of lion

Raginpert, Raghinpert, Reginbert, Regimbert, Raginpert – raginis + pertas – “born of the horned one” or “horned-born”

Ansprand, Anprand – anas + prandas – he rituals (praudas – custom, quote from lkz.lt)

Liutprand, Luitprand – ritual of lion

Hildeprand, Utprand, Ildebrando, Ildeprando, Ilprando – wolf prandas, ilelis (ylelis?) – ritual of wolf (quote from lkz.lt)

Ratchis, Rachis, Ratgis, Radics – radinti, radinys – a finding

Aistulf, Ahistulf, Aistulfus – aistrinti + ulpas – sound of passion

What German equivalents can be found for these Lombard king names?

The names of Lombard and Gothic princesses contain the characteristic root ‘holy’. This corresponds to the Lithuanian word šventas/šventa (in the Northeastern dialect – svintas/svinta). The names of queens and princesses include the following:

Matasvinta (Matasuntha, Matesvinta, Matesuentha), Amalasvinta (Amalasventa), Godswinth, Goiswintha (Gaisvinta, Goiswentha, Goisventa, Goisuintha, Godiswintha), Galswintha (Gelesvinta, Gelesventha), Nemilaswinta (Nemilasvinta), Clodoswinthe (Chlotoswinda, Clodoswenthe; fille de Sigebert Ier), Albsvinda (Albswintha), Clodoswinthe (fille de Clotaire Ier), Glothsuinda.

The names of these Gothic kings also have the same root – Holy or Saint:

Swinthila, Chindaswinth, Reccesvinthus.

In the “New Geographical Dictionary”, published in Latin in 1738, the name of the Lombards is written as Laucobardi:

Lombardi, laucobardi, longobardi — populi Italię.

Philippus Ferrarius: „Novum lexicon geographicum…“ 1738, 382 p.

This is very reminiscent of the Baltic tribe of the Bartians and the word “laukas” (field). Perhaps the Lauco Bartians lived in fields — somewhere in the fields or plains of present-day Poland.

So much for the “Germanicness” of the Lombards.

Cover image. Laveno is the only point for transporting cars across Lake Maggiore. The Lithuanian word for ‘ship’ is laivas, but some dialects or poetic forms may use laivė.

Study of the Lombard language based on GIS analysis, historical geography, place names, numismatics, genetic research:

Study of the Lombard language based on GIS analysis, historical geography, place names, numismatics, genetic research: